I recently came back to C++ development for the first time in 7–8 years; in many ways, for the first time ever. What follows is something I wrote when I finally began to understand the development workflow for C++. I hope it will help other students and newcomers to C++ pick out their preferred toolchain for comfortable and productive development.

—Neil

Table of Contents

- What is a Toolchain?

- What is a Development Environment?

- Notes on Text Editor Choice

- Notes on Compiler Choice

- Notes on Build Management Choice

- Notes on Debugger Choice

- Summing It Up

What is a Toolchain?

There are two major uses of the word toolchain. Its use in reference to C/C++ typically signifies a collection of tools used to build a program; a chain of transformations which takes the C++ source code to binary machine opcodes (you thought that this was what a compiler does, but in fact the compiler is only one piece of this process). More generally, the term is also used to refer to the set of software tools and utilities a programmer chooses to assist them in development. Here, we will refer to this broader category as one's development environment. So when I say toolchain, I mean the choice of compiler and build tools, which is a subset of your development environment.

When you begin C++ development, you are thrown into the deep end. You need to choose what tools you're going to use for development, before you even know what the tools are used for. This choice is strongly affected by which operating system you use, which operating system you want your program to run on, whether you choose up-front setup cost in return for easier development, and other deeply personal preferences. The goal of this tutorial is to give you the background you need to choose wisely, plus some sensible recommendations to get you started.

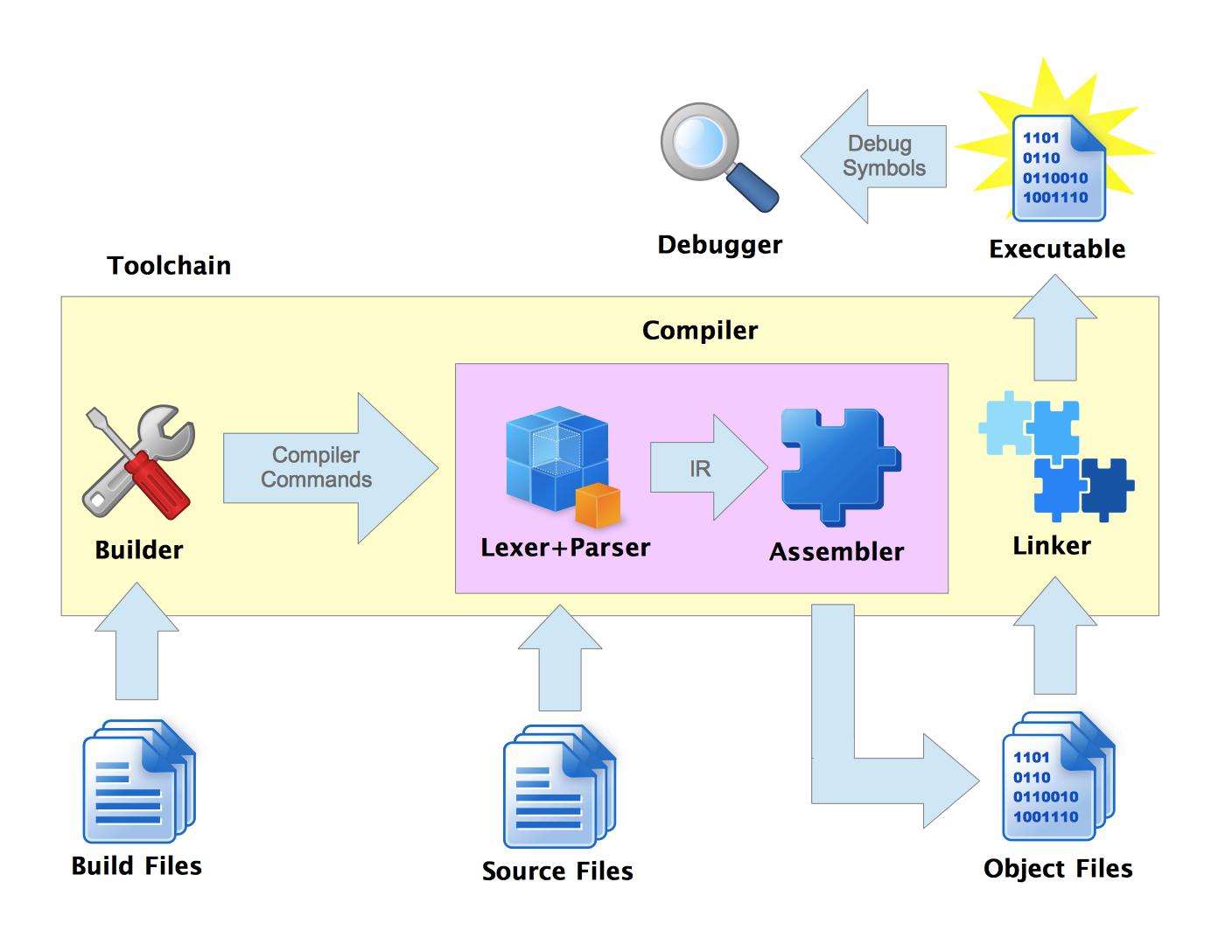

A toolchain, then, is a chain of tools: the major components of a toolchain are builder, compiler, linker, and debugger. This is how they work together:

To make this example concrete, here are the GNU equivalents of the above components:

| Builder | make |

| Compiler | g++ |

| Linker | ld |

| Debugger | gdb |

The GNU toolchain is generally the de facto option for C++ development on any operating system and any processor. It's generally a good recommendation for anything you need to accomplish. When in doubt, use GNU.

What is a Development Environment?

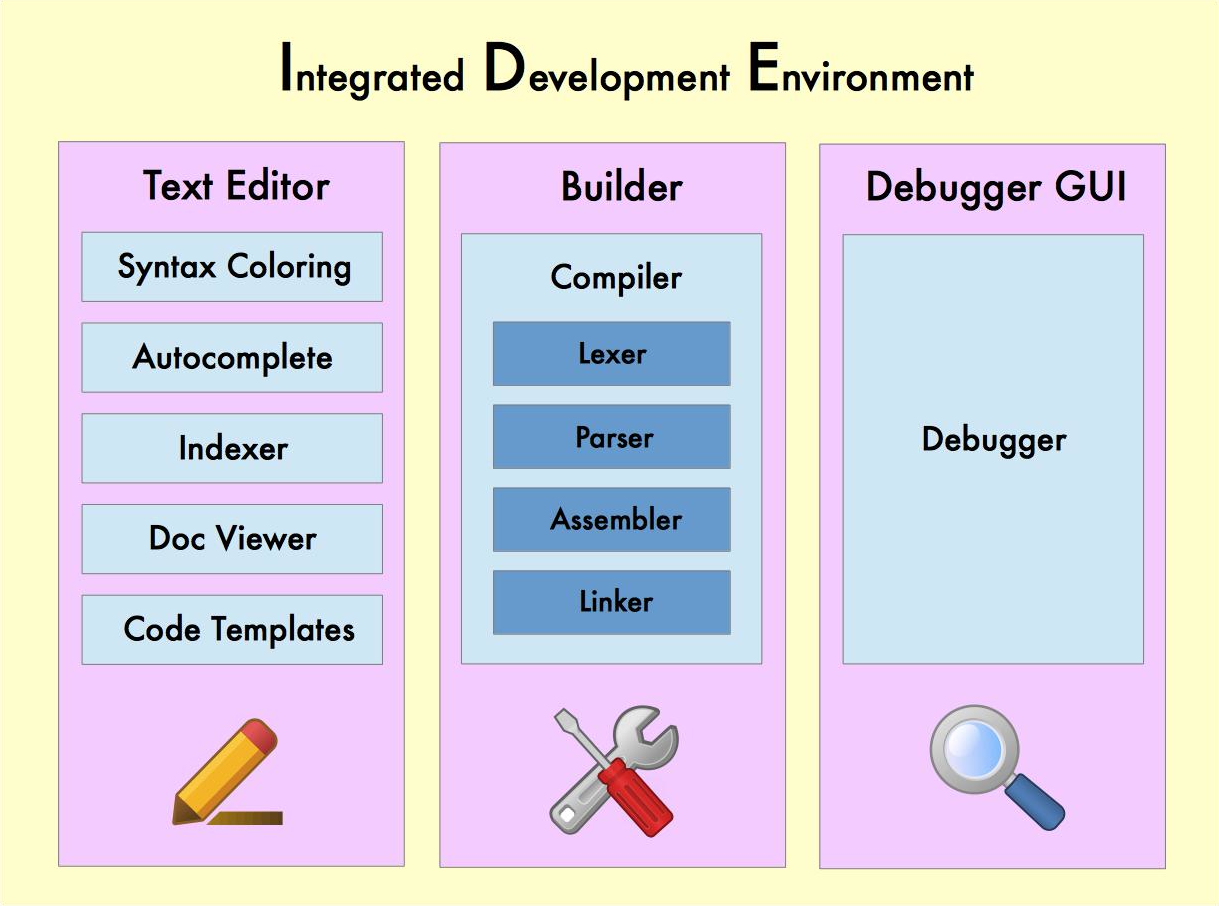

As I'm referring to it, a development environment is nothing other than your tool belt as a programmer. It is the entire corpus of software utilities you use to get stuff done. Primarily what we'll focus on in this tutorial are text editors, compiler toolchains, build tools, and debuggers. Often these are all wrapped up in a single package, called the Integrated Development Environment (IDE).

There are two main choices when it comes to development environment. From what I've seen, seasoned software practitioners in industry are pretty equally split between these options. I think either of them would be a great choice for a newcomer. They are:

- An integrated development environment.

- Emacs or Vim, combined with make or CMake, plus a debugger.1

I hope to educate you in the various nuances of these choices, and give you just enough information to start your own quest for your C++ holy grail. Here is the sequence of tasks I put before you:

- Determine what OS you'll be doing development on (your host machine).

- Determine what OS(es) you'd like your program to run on (your target machine) (for CPSC 221 students, this includes Linux!).

- Pick a text editor (for the host machine) (ideally works on the target as well).

- Pick a compiler (for the target machine).

- Pick a build management tool (for the target machine).

- Pick a debugger (for the target machine).

It's often the case that you're concerned with supporting only one OS, and you don't need to worry about the difference between host machine and target machine. But in the case of our class, even if you do not use Linux as your host machine, you must ensure that it is one of your target machines, because that is what our TAs will use to compile and run your programs! In other cases, you'll want to support all the major operating systems, because you'll want the whole world to adopt your program, right?! This can become difficult with a language that compiles to machine code, like C++. You'll need to make sure to pick a set of build tools that works on all platforms. This usually boils down to the GNU toolchain.2

Notes on Text Editor Choice

Your text editor is your main weapon in the mean streets of programmerdom. In many ways it will define your style, your strengths, and your weaknesses. Will you become a master of the timeless emacs-fu? Will you artfully slice and dice a bit of source code with sublime text kendo? Or will you employ the secrets of IntelliJitsu to amaze your friends and confound your enemies? An editor is not the full martial art—it's only a weapon—but it will do much to influence your style. Just as Bruce Lee rejected studying a single martial art in favor of borrowing techniques from all over, you should eventually try a few of these tools.3

My advice is to try a couple different ones in the next few weeks, then commit to one for the next year or so. If you continue down the path of software development, you will inevitably master many of these tools, so don't worry about making the perfect choice.4

As stated above, your main choice is to decide between a full-blown IDE on the one hand, or a text editor + build tool + debugger combo on the other. We can safely assume you'll use make + gdb as your build tool + debugger, so the only real choice is this: IDE or text editor? The main trade-off here is setup time vs. feature richness.

An IDE will ultimately allow you to be more productive, but involves an initial setup cost in terms of configuring the project.5 If you can get past that point, you have access to a world of features that are not afforded to text editors, or can only be had through a hodgepodge of plugins. These features include indexing, autocompletion, refactorings, in-editor documentation, code templates, and more. An IDE does more than simply unite the basic pieces of a development environment—it adds many utilities on top of that.

A text editor is easier to get started with, especially if you are working on someone else's project. In this case you don't have the pain of figuring out how to get your IDE to build their project; you just use whatever build process they used. However, there are some text editors which are not so easy to get started with, yet are more powerful, so I should make some further distinctions.

There are two types of text editor. One is a graphical editor like GEdit, Notepad++, or Sublime Text. The other is a command-line editor like Emacs or Vim. Most graphical editors don't bring the amazing range of functionality that an IDE provides. So these are the easiest to learn, but also the most limited. They are generally not used by folks in industry.[citation needed] In contrast, the CLI editors can be as feature-rich as an IDE. But it takes a long time and a lot of customization to make them that way. This is both good and bad. Many people get off on this.6 An IDE is ultimately easier to master than one of these editors, but once again, involves more initial setup time.

The CLI editors have one major advantage that should not be missed: they are already installed on pretty much every Unix/Linux distribution you'll ever use. Whether you need to ssh into a Linux server to edit some config files for a website, or you need to telnet into a robot to edit its source code, being proficient with one of these editors is a huge boon to your programming life. Even if you use an IDE for most programming tasks, you will probably need to use one of the CLI editors eventually.

Bottom Line: Whichever way you choose, the main point to remember is that IDEs will require more babysitting, but give you more bang for your buck. They are likely to be more difficult in the outset, but much easier after the initial setup.7

Notes on Compiler Choice

Just like choosing a debugger (below), you'll either use the default supplied by your IDE, or you'll use the GNU toolchain. GNU provides gcc for C development and g++ for C++ development. At the end of the day, g++ is just a wrapper around gcc. Whatever compiler you choose for yourself, you must also ensure your code works with the GNU compiler, because that is what we will use to grade you in this course. This normally works fine as long as you don't accidentally use some Mac- or Windows-specific libraries.

There is also a relatively new toolchain (new as in 2003) called LLVM. The compiler for LLVM is called Clang, and is rapidly gaining popularity (in fact, clang has replaced g++ on OS X). Clang gives nicer error output and may actually be very helpful for a beginner. As far as I know, it accepts most of the same options as g++ so you can start using it as a drop-in replacement. You might want to check it out.

Bottom Line: Use g++ (or whatever your IDE provides).

Notes on Build Management Choice

Here are your choices when it comes to build management:

- IDE builder

- CMake

- Autotools

- Make

- your own blood, sweat, tears, etc.

One of the biggest advantages an IDE typically brings is automated build management. Without an IDE, you need to compile your code yourself, with handwritten calls to a compiler. The good folks at GNU have come up with a terrible, barely-working solution to this problem. Instead of tediously writing compiler commands yourself, you tediously write them into a Makefile. That way, at least you only have to do it once. But you do still have to do it yourself. And you need to change it every time you add a new source file. And it often varies from machine to machine.

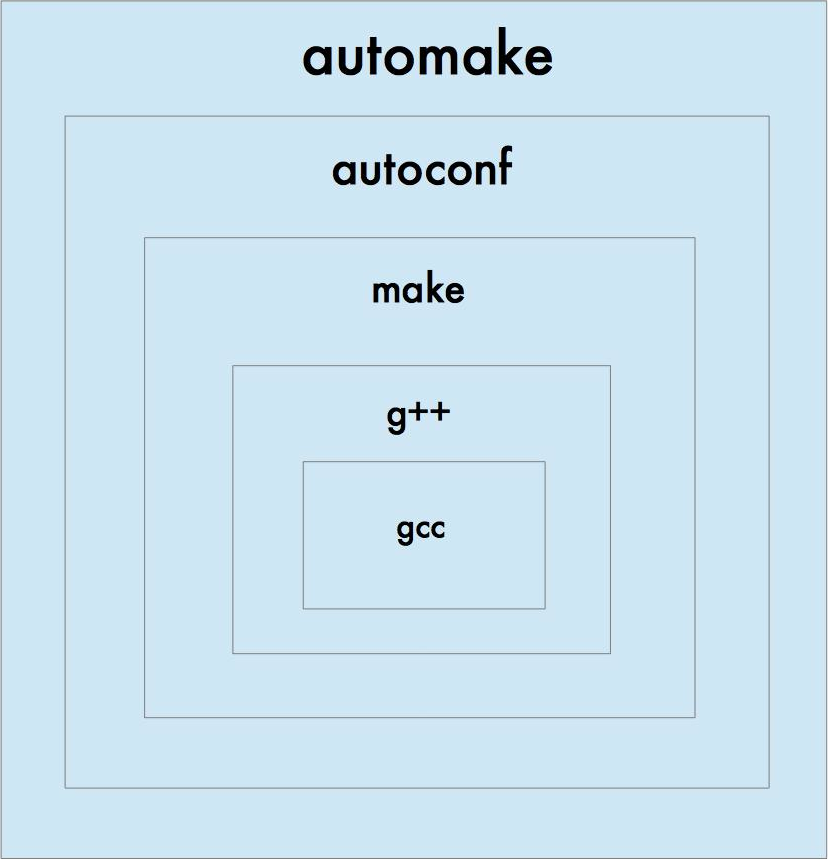

The state of affairs in C++ build management is so bad that there is yet another tool that runs on top of make, called Autotools, that attempts to make the process bearable. In my opinion, it doesn't really achieve this goal. Here's how it works. You write configure.ac files and Makefile.am files for automake. automake generates the files needed for autoconf, which generates the makefiles you need, which are used by make to generate compiler commands, which is what you actually wanted in the first place.

There is another build manager which does somewhat better, called CMake. It directly generates makefiles, and has very nice formatted output, though it is still rather difficult to use.8 When you start a larger project, you may want to check it out. For now, you can leave it.

Bottom Line: Choose an IDE or lightweight makefiles ... for now. Oh, and here's another diagram:

C++ build management: infinite recursion

Notes on Debugger Choice

The debugger situation can get a bit confusing, because there's many debugger front ends but few actual debuggers. There's essentially only three debuggers out there, and they are:

- GDB (GNU toolchain)

- LLDB (LLVM toolchain)

- CDB (Windows toolchain)

It can also be confusing because each C++ toolchain provides its own debugger. So do you have to use the debugger that matches your compiler? As it turns out, no. Debuggers are completely compiler-agnostic; they depend on the binary format, which is determined by the OS. For example, all compilers that work on Unix produce binaries in the same format, the ELF format, and most of them provide debugging flags in the same format, the DWARF format (you can tell these things were invented by a bunch of geeks). All Unix debuggers know how to interpret these formats. So nothing prevents you from compiling with g++ and debugging with lldb, or compiling with clang and debugging with gdb.9

If you use an IDE, the choice of debugger is already made. The IDE serves as a GUI for one of the above debuggers. Otherwise, you'll generally choose GDB, or a GUI front-end for GDB (GNU wins again). It's been around for a long time and has wide support. LLDB is a new, improved choice which is almost ready for adoption, but it doesn't yet have any GUIs that support it. Still, if you plan to work command-line-only and GUI-free, you may want to give it a look.

Bottom Line: Use what your IDE provides, or use GDB.

Summing It Up

It's my recommendation that you try Emacs, Vim, or an IDE. Any one of these will be a valuable part of your toolbelt in a career in software engineering, and even in further computer science courses. Still, it can be a lot to learn a whole new toolset all at once, while at the same time learning a new language. You may prefer to find a powerful text editor with a more gradual learning curve, so that's okay too. I won't make any specific recommendations here (although I did in the footnotes). You can find many opinions online about which text editors are most popular.

In terms of a builder, you should probably use Make for now. There are other options to look into when your projects become bigger.

In terms of everything else, either use your IDE's default toolchain, or use the GNU toolchain. But look out in the near future for the LLVM toolchain; I think its tipping point is upon us.

All the best on your quest, and Happy Coding!

This article was originally posted here.- You could replace the use of "Emacs or Vim" here with any text editor of your choosing. Sooner or later, I think you will have to learn one of the choices I've given (Emacs, Vim, or IDE). Your choice, then, is whether you want that to be "sooner" or "later."

- At the very least, it means you need to be careful not to use any platform-specific libraries in your source code. Other times, you'll only have one target machine but it will be different from your host machine, because the target is a robot, or an airplane, or a DVR. You can't exactly do development on those machines; you need to cross-compile from host to target. As a beginner, you don't need to worry about these more complex setups too much—but now that I've mentioned them, hopefully they won't mystify you if you see them mentioned on a website somewhere.

- That advice applies tenfold to programming languages.

- I myself hold black belts in both Eclipse and IntelliJ, and something like a blue belt in Vim and Sublime Text.

- If you are creating a project from scratch, then using the IDE's "hello world" template will avoid most of this pain and have you started very quickly. Trying to build some existing source code can be trickier.

- See also: yak shaving.

- Let me reemphasize my opinion that you should jump right in and use Emacs, Vim, or an IDE. I think you will end up learning these at some point before you graduate. Still, learning a whole new development environment while also learning a new programming language is daunting. If it's too much right now, may I recommend you try Sublime Text. At the time of writing, it's pretty new to the scene, yet already a favorite among those in the know.

- Believe it or not, I actually use CMake to generate my Eclipse project files, and then I use Eclipse for development. And I'm not alone. I gather that most people in the robotics industry use this toolchain. Just goes to show how messed up C++ development is.

- Supposedly. Theoretically. In an ideal world.